Long before formal background checks, humans relied on reputation systems to evaluate trustworthiness. Small communities knew everyone’s history intimately. Strangers needed letters of introduction from trusted intermediaries. Merchants belonged to guilds that vouched for their integrity. These informal systems served the same function as modern background checks: helping people make informed decisions about whom to trust.

The key difference was scale and memory. In pre-modern societies, reputation was local, oral, and subject to redemption. Move to a new town, and you could often start fresh. Prove yourself over time, and old mistakes could be forgiven and forgotten.

Early Written Records

Written records changed everything. Ancient civilizations began documenting criminal punishments, debt obligations, and civic status. Roman records tracked citizenship, property ownership, and legal judgments. Medieval guilds maintained membership rolls and disciplinary records.

These written systems represented early forms of background checking. Before accepting an apprentice, guild masters consulted records. Before extending credit, merchants verified previous dealings. The permanence of writing created accountability but also reduced opportunities for fresh starts.

The Wanted Poster Era

The 19th century brought mass production printing, enabling new approaches to tracking criminals. Wanted posters could be copied and distributed widely, creating the first mass-scale background check system. For the first time, someone’s criminal history could follow them across regions.

Photography intensified this change. Faces could be documented and recognized, making disguise and reinvention more difficult. The combination of printed descriptions and photographic images created unprecedented surveillance capabilities for the era.

The Pinkerton Innovation

Private detective agencies like Pinkerton’s emerged in the mid-1800s, offering background investigation services to businesses. Companies hiring managers or handling money wanted assurance that employees wouldn’t steal. Railroads, banks, and large retailers became early adopters of systematic employee screening.

These private investigations were thorough but expensive, limiting background checks to sensitive positions. Most hiring remained informal, based on personal references and interviews rather than documented investigation.

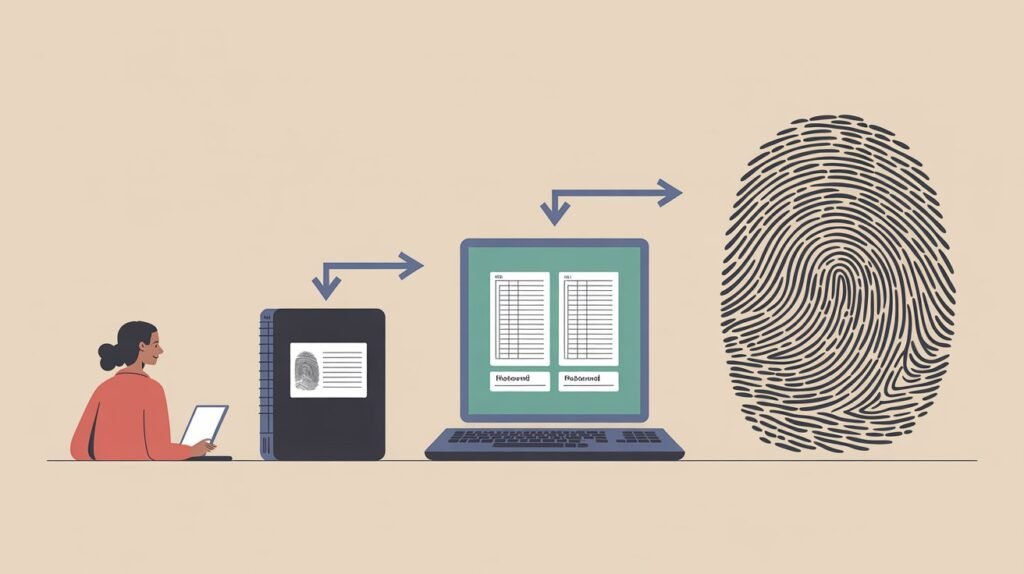

Fingerprinting Revolution

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw fingerprinting develop as a reliable identification method. This technology solved a persistent problem: how to definitively connect criminal records to specific individuals. Names could be changed, appearances altered, but fingerprints remained unique.

Criminal background checks became more reliable and harder to evade. The first centralized fingerprint databases emerged, allowing information sharing across jurisdictions. Someone arrested in one state might now have that record available when applying for work in another.

Credit Bureaus Emerge

The 20th century brought credit bureaus, initially local operations tracking who paid debts and who defaulted. These expanded into national systems, creating the first comprehensive civilian background check infrastructure. For the first time, ordinary people’s financial behaviors were systematically documented and shared.

Credit checks became routine for loans, housing, and eventually employment. Your financial history became inseparable from your identity in ways previous generations never experienced. The credit report represented a new kind of permanent record.

Computing Changes Everything

Computers transformed background checks from labor-intensive investigations to instant queries. Information that once required weeks of correspondence between agencies could now be retrieved in seconds. Databases that were isolated are now connected, creating comprehensive views of individual histories.

Background checks Australia and worldwide became faster, cheaper, and more thorough with digital systems. This democratization meant screening expanded from high-security positions to routine employment, volunteer work, and housing applications.

The Internet Explosion

The internet multiplied available information exponentially. Public records went online. Commercial databases aggregated information from countless sources. Social media created voluntary documentation of beliefs, activities, and associations.

Modern background checks access dozens of databases simultaneously: criminal records, credit reports, employment histories, educational credentials, professional licenses, property records, and more. The scope would astonish someone from even the 1980s.

Regulatory Responses

As background checks became ubiquitous, regulations emerged to protect fairness and accuracy. The Fair Credit Reporting Act in the United States established standards for background check companies. Various Australian consumer protection laws addressed similar concerns about accuracy, consent, and use.

These regulations acknowledge that background checks wield significant power over people’s lives. Wrong information or unfair use can deny housing, employment, and opportunities. Legal frameworks attempt to balance legitimate screening needs with individual rights.

The Personal Background Check

A uniquely modern development is people checking themselves. Services now allow individuals to see what appears in their background checks before employers or landlords run them. This transparency would have been impossible in earlier eras when background information flowed one direction: from investigators to decision makers.

Self-checking allows people to correct errors, understand what others will see, and prepare explanations for negative findings. This shifts some power back to the subjects of investigation.

Globalization Challenges

International background checks present new complications. Someone working in background checks in Australia might have criminal records in another country. Verifying foreign educational credentials challenges even sophisticated screening systems. Different national privacy laws restrict information sharing.

These challenges have spawned international background check services attempting to navigate varied legal systems, languages, and record keeping standards. The task is complex, and gaps remain common.

The Expungement Movement

Recent years have brought growing recognition that permanent records are problematic. Expungement and record sealing laws allow people to petition for removal of old offenses. This represents a philosophical shift: acknowledging that background checks should have temporal limits.

The movement connects to broader conversations about rehabilitation, second chances, and the purposes of criminal justice. If punishment includes permanent unemployability, is that just or counterproductive?

Algorithmic Screening

The latest evolution involves artificial intelligence analyzing background check data. Algorithms assess risk based on patterns across thousands of variables. This creates new efficiency but also new concerns about bias, opacity, and accountability.

Machine learning systems may perpetuate historical discrimination or identify spurious correlations. Understanding how algorithmic screening makes decisions becomes nearly impossible, even for the programmers creating these systems.

Coming Full Circle

Interestingly, some trends now circle back toward earlier approaches. Emphasis on personal references, character letters, and holistic evaluation represents recognition that pure data doesn’t capture human complexity. LinkedIn and professional networking sites create new forms of reputation systems reminiscent of pre-modern guild endorsements.

These developments suggest that even with perfect information technology, human judgment remains essential. Background checks provide data, but interpreting that data requires wisdom, context, and recognition of human capacity for change.

The Human Element Persists

Throughout this entire history, from wanted posters to instant digital reports, one constant remains: background checks are ultimately about humans trying to understand other humans. Technology changes the speed, scope, and accuracy of information gathering, but the fundamental questions persist.

Can we trust this person? What does their past predict about their future? How do we balance safety with opportunity? When do we allow redemption? These questions connect every era of background checking, reminding us that despite technological transformation, the human elements of trust, judgment, and second chances remain eternally relevant.

Want more to read? Visit dDooks.